Mary Harris Jones

| Mother Jones | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | May 1, 1837 Cork, County Cork, Ireland |

| Died | November 30, 1930 (aged 93) Silver Spring, Maryland, United States |

| Occupation | Labor and community organizer |

Mary Harris "Mother" Jones (August 1, 1837 – November 30, 1930), born in Cork, Ireland, was a prominent American labor and community organizer, who helped co-ordinate major strikes and co-founded the Industrial Workers of the World. Her activities were done under the moniker of Mother Jones, after which Mother Jones magazine is named.

Contents |

Biography

She was born Mary Harris, the daughter of a Roman Catholic tenant farmer, Richard Harris and his wife Ellen Cotter, on the northside of Cork city, Ireland.[1] Some recent materials list her birthday as August 1, 1837, although she claimed her birthdate to be May 1, 1830. Her claims to an earlier date may have been an appeal to her grandmotherly image. The date of May 1 was possibly chosen symbolically, to represent the national labor holiday and anniversary of the Haymarket affair.[2]

Formative years

Jones emigrated with her family to Canada when she was roughly fourteen or fifteen years old.[3] The young Mary acquired a Catholic education in Toronto before her family moved to the United States.[3] She became a teacher in a convent in Monroe, Michigan. After becoming tired of her assumed profession, she moved first to Chicago and later to Memphis, where she married George Jones, a member of the Iron Workers' Union, in 1861.[4] She eventually opened a dress shop in Memphis on the eve of the Civil War.[3]

Two turning points in her life were the 1867 deaths of her husband and their four children (all under the age of five) during a yellow fever epidemic in Tennessee, and the 1871 Great Chicago Fire. After her entire family succumbed to the disease, she returned to Chicago to begin another dressmaking business.[5] She lost her hard-earned home, shop and possessions in the Great Fire. This second loss catalyzed an even more fundamental transformation: she turned to the nascent labor movement and joined the Knights of Labor, a predecessor to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies").[6] The Haymarket Riot of 1887 and the fear of anarchism and revolution incited by union organizations led to the rapid demise of the Knights of Labor. Once the Knights ceased to exist, Mary Jones became largely affiliated with the United Mine Workers. With the UMW, she frequently led strikers in picketing and encouraged the striking workers to stay on strike when the management brought in strike-breakers and militias.[4] As another source of her transformation into a radical organizer, biographer Elliott Gorn draws out her early Roman Catholic connection – including bringing to light her relationship to her estranged brother, Father William Richard Harris, Roman Catholic teacher, writer, pastor, and dean of Toronto's diocese of St. Catherine's, who was "among the best-known clerics in Ontario."[6] It is likely that Mary Jones’ political views were also shaped by the 1877 railroad strike, Chicago’s radical labour movement, and the Haymarket Riot and depression of 1886.[3] Active as an organizer and educator in strikes throughout the country at the time, she was particularly involved with the UMW and the Socialist Party of America. As a union organizer, she gained prominence for organizing the wives and children of striking workers in demonstrations on their behalf. She became known as "the most dangerous woman in America," a phrase coined by a West Virginia district attorney, Reese Blizzard, in 1902, at her trial for ignoring an injunction banning meetings by striking miners. "There sits the most dangerous woman in America", announced Blizzard. "She crooks her finger—twenty thousand contented men lay down."

Mary Jones was ideologically separated from many of the other female activists of the pre-Nineteenth Amendment days due to her aversion to female suffrage. She was quoted as saying that “You don’t need the vote to raise hell!”[7] Her opposition to women taking an active role in politics was based on her belief that the neglect of motherhood was a primary cause of juvenile delinquency.

Jones became known as a charismatic and effective speaker throughout her career.[8] She was a storyteller, who would liven her rhetoric with real and folk-tale characters, punctuate with participation from audience members, flavour it with passion, and include humor-ridden methods to rile up the crowd such as profanity, name-calling, and wit. Occasionally she would include props, visual aids, and dramatic stunts for effect.[8] By the age of sixty, she had effectively assumed the persona of Mother Jones by claiming to be older than she actually was, wearing outdated black dresses and referring to the male workers that she supported as ‘her boys’. The first reference to her in print as ‘Mother Jones’ was in 1897.[3]

Children's Crusade

In 1901, the workers who were employed in the Pennsylvania silk mills went on strike, many of them being young female workers who were demanding they be paid adult wages.[9] John Mitchell, the president of the UMWA, brought Mother Jones to north-east Pennsylvania in the months of February and September to encourage unity among the striking workers. To do so, she encouraged the wives of the workers to organize into a militia, who in turn would wield brooms, beat on tin pans and shout “Join the union!”[9] Jones believed that these wives had an important role to play as the nurturers and motivators of the striking men, but not as fellow workers. She made claim that the young girls working in the mills were being robbed and demoralized.[9] To enforce worker solidarity, she travelled to the silk mills in New Jersey and returned to Pennsylvania to report that the conditions she observed were far superior. She stated that “the child labor law is better enforced for one thing and there are more men at work than seen in the mills here.”[9] In response to the strike, mill owners also divulged their side of the story. They claimed that if the workers still insisted on a wage scale, they would not be able to do business while paying adult wages and would be forced to close down.[10] Even Jones herself encouraged the workers to accept a settlement. Although she agreed upon a settlement which sent the young girls back to the mills, she continued to fight child labor for the remainder of her life.[11]

In 1903 Jones organized children, who were working in mills and mines at the time, to participate in the "Children's Crusade", a march from Kensington, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Oyster Bay, New York, the home of President Theodore Roosevelt, with banners demanding "We want to go to School and not the mines!" As Mother Jones noted that many of the children at union headquarters had missing fingers and other disabilities, she attempted to get newspaper publicity about the conditions in Pennsylvania regarding child labor. However, the mill owners held stock in essentially all of the newspapers. When the newspaper men informed her that they could not advertise the facts about child labor because of this, she remarked “Well, I’ve got stock in these little children and I’ll arrange a little publicity.”[12] Permission to see President Roosevelt was denied by his secretary and it was suggested that Jones address a letter to the president requesting a visit with him. Even though Mother Jones wrote a letter for such permission, she never received an answer.[13] Though the President refused to meet with the marchers, the incident brought the issue of child labor to the forefront of the public agenda. Mother Jones's Children's Crusade was described in detail in the 2003 non-fiction book, Kids on Strike!.

In 1913, during the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike in West Virginia, Mother Jones was charged and kept under house arrest in the nearby town of Pratt and subsequently convicted with other union organizers of conspiring to commit murder, after organizing another children's march. Her arrest raised an uproar and she was soon released from prison, after which, upon motion of Indiana Senator John Worth Kern, the United States Senate ordered an investigation into the conditions in the local coal mines.

A few months later she was in Colorado, helping to organize the coal miners there. Once again she was arrested, served some time in prison and was escorted from the state in the months leading up to the Ludlow Massacre. After the massacre she was invited to Standard Oil's headquarters at 26 Broadway to meet face-to-face with John D. Rockefeller, Jr., a meeting that prompted Rockefeller to visit the Colorado mines and introduce long-sought reforms.

Later years

By 1924, Mother Jones was in court again, this time facing charges of libel, slander and sedition. In 1925, Charles A. Albert, publisher of the fledgling Chicago Times, won a $350,000 judgment against the matriarch.

Mother Jones remained a union organizer for the UMW into the 1920s and continued to speak on union affairs almost until her death. She released her own account of her experiences in the labor movement as The Autobiography of Mother Jones (1925).

In her later years, Jones lived with her friends Walter and Lillie May Burgess, on their farm in what is now Adelphi, Maryland. She celebrated her self-proclaimed 100th birthday there, on May 1, 1930 and was filmed making a statement for a newsreel. She died at the age of 93 or 100 on November 30, 1930.[14]

She is buried in the Union Miners Cemetery in Mount Olive, Illinois, alongside miners who died in the Virden Riot of 1898.[15] She called these miners, killed in strike-related violence, "her boys."[16]

Legacy

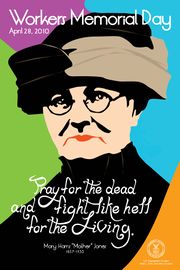

Amidst the tragic, and sometimes fatal, violence directed at early trade unionists, Mother Jones uttered words still invoked by union supporters more than a century later: "[p]ray for the dead and fight like hell for the living." Already known as "the miners' angel," when she was denounced on the floor of the United States Senate as the "grandmother of all agitators," she replied:

I hope to live long enough to be the great-grandmother of all agitators.

During the bitter 1989–90 Pittston Coal Strike in Virginia, West Virginia and Kentucky, the wives and daughters of striking coal miners, inspired by the still-surviving tales of Mother Jones' legendary work among an earlier generation of the region's coal miners, dubbed themselves the "Daughters of Mother Jones." They played a crucial role on the picket lines and in presenting the miners' case to the press and public.[17]

The magazine Mother Jones was established in the 1970s and quickly became the largest selling radical magazine of the decade.[18] Each issue divulges information on the themes that were important to Jones herself, such as corporate corruption, political collapse, small-is-beautiful, communal living and feminism.

Mary Harris "Mother" Jones Elementary School, in Adelphi, Maryland, is named in her honor.[19]

Students at Wheeling Jesuit University in West Virginia can apply to reside in Mother Jones House, an off-campus service house. Residents perform at least ten hours of community service each week and participate in community dinners and events.

To coincide with International Women's Day on 8 March 2010 a proposal was made by Councillor Ted Tynan for a plaque to be erected in Mary Harris Jones' native city of Cork in Ireland. The proposal is currently before Cork City Council.[20]

Music and the arts

In The American Songbag, Carl Sandburg suggests that the "she" in "She'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain" was a reference to Mother Jones and her travels to Appalachian mountain coal mining camps promoting the unionization of the miners.[21]

"The Death of Mother Jones", a song whose authorship is unknown, was first recorded by Gene Autry in 1931, in what may have been his first recording session.

"Union Maid", a song by Woody Guthrie, calls for women to emulate Mother Jones by fighting for both women's rights and workers' rights.

Books

- The Autobiography of Mother Jones. Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Col, 1925.

- Mother Jones Speaks: Speeches and Writings of a Working-Class Fighter. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1983, ISBN 0-87348-810-5

- Mother Jones and the March of the Mill Children. Brookfield , CT: Colman, Penny. The Millbrook Press, 1994

Notes

- ↑ Day by Day in Cork, Sean Beecher, Collins Press, Cork, 1992

- ↑ http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h750.html

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Eric Arnesen, "A Tarnished Icon," Reviews in American History 30, no. 1 (2002): 89

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Russell E. Smith, "March of the Mill Children", The Social Service Review 41, no. 3 (1967): 299

- ↑ ric Arnesen, "A Tarnished Icon," Reviews in American History 30, no. 1 (2002): 89

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America, Elliott Gorn

- ↑ Russell E. Smith, "March of the Mill Children", The Social Service Review 41, no. 3 (1967): 298

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Mari Boor Tonn, "Militant Motherhood: Labor's Mary Harris 'Mother' Jones," Quarterly Journal of Speech 81, no. 1 (1996): 2

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Bonnie Stepenoff, "Keeping it in the Family: Mother Jones and the Pennsylvania Silk Strike of 1900-1901,” Labor History 38, no. 4 (1997): 446

- ↑ Bonnie Stepenoff, "Keeping it in the Family: Mother Jones and the Pennsylvania Silk Strike of 1900-1901,” Labor History 38, no. 4 (1997): 448

- ↑ Bonnie Stepenoff, "Keeping it in the Family: Mother Jones and the Pennsylvania Silk Strike of 1900-1901,” Labor History 38, no. 4 (1997): 448

- ↑ Russell E. Smith, "March of the Mill Children", The Social Service Review 41, no. 3 (1967): 300

- ↑ Russell E. Smith, "March of the Mill Children", The Social Service Review 41, no. 3 (1967): 303

- ↑ Death Notice for Mother Mary Jones, The Washington Post, Dec 2, 1930, pg. 3.

- ↑ "Service Tomorrow for Mother Jones," The Washington Post, Dec 2, 1930, pg. 12.

- ↑ http://www.dol.gov/oasam/programs/laborhall/1992_jones.htm

- ↑ The Pittston Coal Strike at www.ic.arizona.edu

- ↑ Michael Andrew Scully, "Would Mother Jones Buy 'Mother Jones'?," Public Interest 53, (1978): 100

- ↑ Mary Harris "Mother" Jones Elementary School home page

- ↑ http://corkpolitics.ie/wp/?p=4509

- ↑ Sandburg, Carl, The American Songbag. 1st ed. NY: Harcourt Brace, 1927.

External links

- DVD and virtual museum about Mother Jones

- Mother Jones: biography by Sarah K. Horsley

- Free eBook of The Autobiography of Mother Jones

- Free audio book of The Autobiography of Mother Jones at Librivox.org

- Mother Jones at Find-A-Grave

- Mother Jones Monument at GuidepostUSA

- Mother Jones Plaque in Adelphi, MD